The problem with the Patricks book

- Greg Nesteroff

- Jul 7, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2025

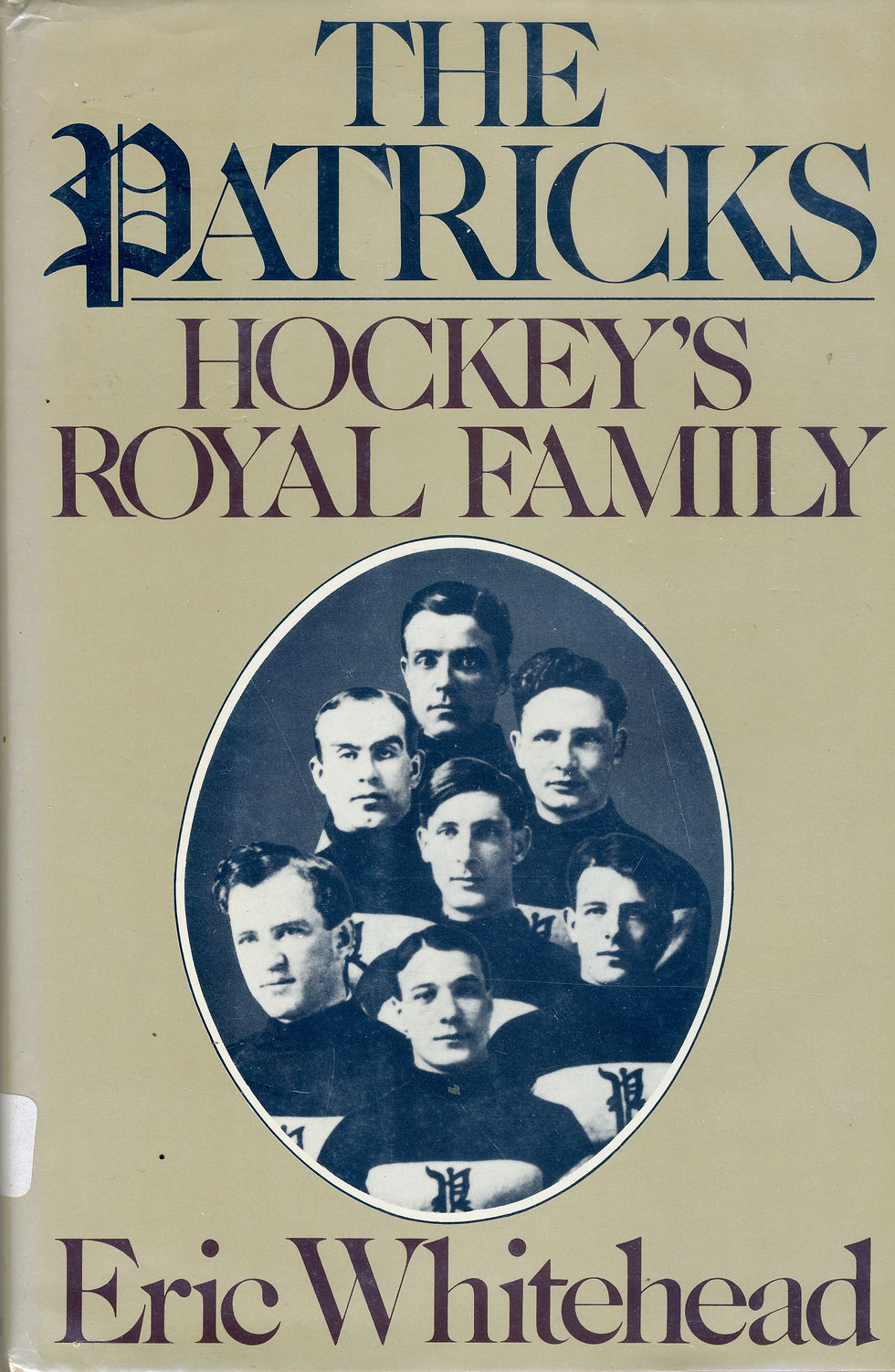

The standard reference book on the Patrick family has long been Eric Whitehead’s The Patricks: Hockey’s Royal Family, published by Doubleday in 1980. A paperback edition came out three years later that for some reason is hard to find. It had a different cover, but I don’t know if there were any changes to the text.

The book is highly entertaining and was well received at the time of its publication. It certainly satiated my interest in the Patricks when I first became curious about them many years ago. But it’s also full of things that aren’t true.

Not uncommon for its era, the book lacked a bibliography or footnotes, although in the preface Whitehead said Cyclone Taylor, whose biography he had previously written, was a “source of intimate material and firsthand anecdotes.” Whitehead also knew Lester Patrick and his sons Muzz and Lynn.

But Whitehead credited a Vancouver cab driver named Boyd Robinson as the book’s catalyst, explaining that Robinson had been “obsessed” with the need for a Patrick family biography. “It was his persistence and support, especially in providing access to an invaluable stock of early historical data collected by the Patricks, that made the writing of this particular journal possible,” Whitehead wrote.

In his own book, The Knights of Winter, Craig Bowlsby explained that Boyd Robinson’s widow, Irene, told him the historical data in question consisted of a trunk of news clippings Robinson had received from Lester’s brother Stan. Robinson later returned the trunk to the Patrick family, but its whereabouts today are unknown. Whitehead also had access to Lester Patrick’s unpublished memoir.

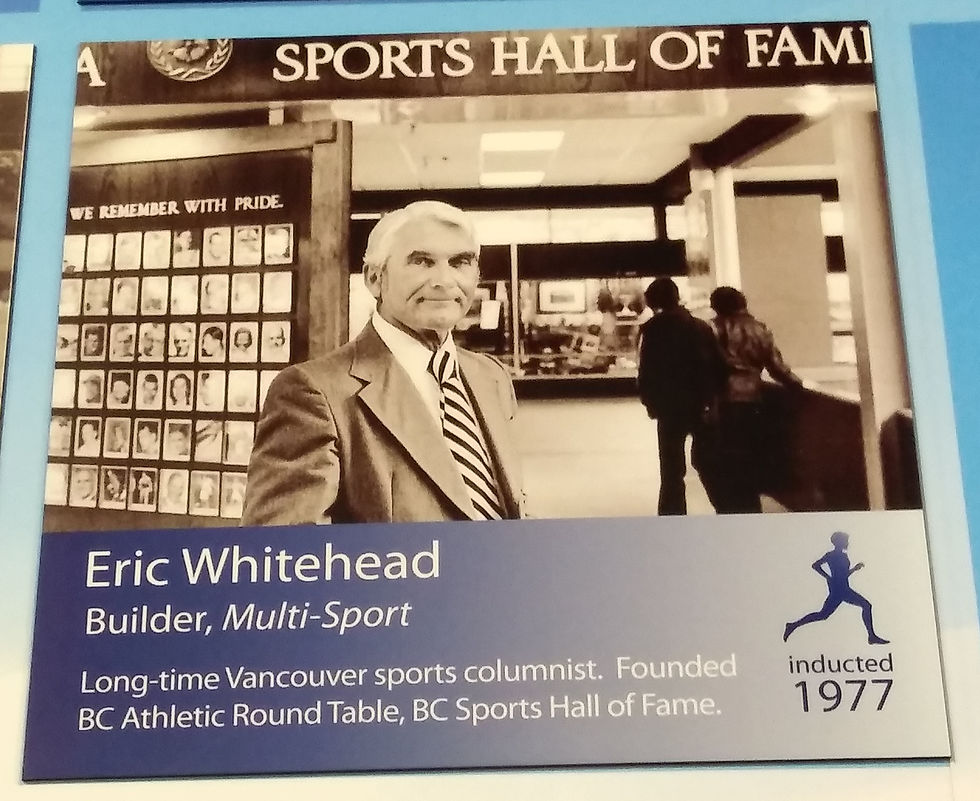

According to his obituary, Whitehead grew up in Detroit and was a writer in Hollywood for the radio show Duffy’s Tavern before joining the Vancouver Province in 1947, where he spent 33 years as a sports columnist.

Whitehead was instrumental in securing the 1954 British Empire Games for Vancouver and the building of Empire Stadium. He started the BC Sports Hall of Fame and was its founding curator. He was inducted into the hall himself, along with members of the Patrick family. Whitehead died in 1993, age 77.

Eric Whitehead as depicted in the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

The errors in his book on the Patricks can be divided into four main categories, the first three of which I consider forgivable, but not the fourth. I haven’t compared the book to any other sports biographies of the same period, so while I’m singling it out for criticism, some of Whitehead’s approaches may have been common to his generation of sportswriters, for whom facts rarely got in the way of a good story. (Jim Coleman, infamously, dreamed up the Curse of Muldoon.)

1) Transcription errors/alterations

Whitehead’s quotes don’t always quite match the original sources. However, in many cases it has no bearing on the overall meaning. So the changes could have been deliberate, accidental, or a bit of both.

I’ve certainly been guilty of this myself, and it’s quite understandable: in the old days, when looking up a newspaper story, you’d squint in front of a microfilm reader, take down notes by hand, and later type up your notes. That left lots of room for error. You might misread a blurry story. You might elide words when transcribing. You might misread your own handwriting when typing.

One example: on p. 175, Whitehead quotes an over-the-top Ottawa Journal headline about Lester’s emergency goaltending stint in the 1928 Stanley Cup playoffs: “Grizzled Veteran Steps into Breach when Chabot Hurt. Fighting Fury Seizes Rangers, Who Repel Maroons. The Heroic Patrick Donned the Pads and Held Off the Reds in Sensational Style.”

The actual headline was: “Grizzled Veteran Steps into the Breach When Chabot Hurt. Fighting Fury Seizes Reckless Rangers Who Repel Maroons. Patrick Dons Pads and Holds Out Red Attack in Sensational Style.”

So it’s pretty close. Whitehead deleted the word “Reckless” before Rangers, added the word “Heroic” before Patrick, changed “Dons” to “Donned,” “holds out” to “held off,” and “Red Attack” to “Reds.” But overall, it doesn’t affect anything.

2) Unreliable second-hand sources

Some sources that Whitehead used led him astray, but you can’t blame him.

In particular, Whitehead relied on an autobiographical series that Frank Patrick wrote for the Boston Globe in 1935 that contained some inaccuracies. For instance, on p. 92, Whitehead said that Lester and Frank “did get back into hockey that winter [1910-11], but only for a couple of games with the Nelson team, in token appearances.” This is based on Frank’s statement: “During 1910-11 … Lester and I played only a couple of games of hockey in the Nelson rink.”

As Craig Bowlsby pointed out in The Knights of Winter, this understates things, for Lester actually played five games and scored 11 goals. Frank played four games and did not score. But it wasn’t as easy in the 1970s to fact check such things. Now, with newspapers.com and other online resources we can often confirm or debunk within seconds. Forty-five years ago, you would have gone blind in front of a microfilm reader, assuming that you even knew where to start looking.

On p. 148, Whitehead writes that when Lester and Eddie Shore met on the ice for the first time in 1925, Lester rocked Shore with such a bone-crunching check that Shore had to be taken off the ice on a stretcher. This wasn’t the case, but at least I traced the source of the story to something Archie Wills wrote in the Victoria Daily Times of Nov. 19, 1949. I’ve written a more extensive account of this incident here.

One other minor example that’s not hockey related: on p. 44, Whitehead says the Nelson opera house once hosted Australian opera singer Dame Melba: “For Melba — a full house with the front rows jammed as usual with the local socialites — tickets were priced at $10, a week’s age for the average working stiff.” In fact, Melba never appeared in Nelson, but I know the book Whitehead got that from. Nelson: Queen City of the Kootenays (1972) claimed Melba had played in Nelson and commanded those prices.

The story seems to have originated in the Nelson Daily News of Nov. 12, 1909, which reported Melba’s manager suggested she would perform there the following year if advance ticket sales were strong. Tickets weren’t $10 apiece, but they were still plenty steep for the times: $5, $4, and $3. Alas, Melba never showed.

But it’s just a scene-setting detail that I wouldn’t expect anyone to spend time verifying.

3) Reasonable but erroneous inferences

Whitehead drew some mistaken conclusions that weren’t necessarily his fault.

For example, on p. 45, he has Lester arriving in Nelson in 1907 and proceeding to the family home at 917 Edgewood Avenue. However, the family didn’t buy this home until 1909, and previously lived at three other places in Nelson.

There’s no way Whitehead could have known that. The 1910 civic directory is the only readily available source of the Patrick family’s Nelson address. Only through some very obscure newspaper items was I able to determine that they had lived in other places, and I still don’t know the exact addresses of two of them.

4) Outright fabrication

This part is more disturbing and not easily dismissed.

In at least a few places, Whitehead just made things up. I don’t mean that he engaged in creative non-fiction, the fairly common practice of recreating scenes based on fact, and perhaps inventing a little dialogue. I mean he quoted from non-existent newspaper accounts, presenting them as real. I don’t know why he felt compelled to do so. The Patrick family story is incredible enough that it doesn’t need embellishment. Perhaps Whitehead’s Hollywood-honed storytelling instincts got the better of him.

Here’s the most egregious example. On p. 62-63, Whitehead described Lester and Frank playing baseball in Nelson “and with Frank moved to third base on the local ball club, this item appeared in the Nelson News:”

Lester Patrick, short-stop, singled home the winning run yesterday as Nelson defeated the University of North Dakota, 5-3. The single was Patrick’s third hit of the game, and the University of North Dakota’s Bill Hennesey, who once played for the Baltimore Orioles in the National league, said that the rangy Nelson short-stop was a fine professional prospect. He said he would so advise the Orioles, if Lester was interested … [ellipsis in original]

The Daily News has been digitized, so it’s easy enough to check this. Nelson did play the University of North Dakota on July 9 and 10, 1909, but the quote above didn’t appear in the newspaper. Frank didn’t play at all. Lester played third base, not short. Nelson did win the first game 5-3, but Lester had one hit, not three. He did bat in a run, but it was the first of the game, not the winning run. He also committed two errors. In the second game, North Dakota won 8-2. Lester was 0-for-4 at the plate and committed another error in the field.

No one named Hennesey played for North Dakota. According to baseball-reference.com, no one named Hennesey has ever played for the Baltimore Orioles. Or in the majors at all, for that matter.

All I can conclude is that Whitehead found Lester’s actual performance underwhelming, so he invented a non-existent player to provide a non-existent quote to make Lester sound more impressive.

Another example of a made-up quote is on p. 58, where Whitehead describes the opening night of the Hall Mines Rink in Nelson of Jan. 18, 1909, in which the home team beat Rossland 14-1. He had the score right, although he said Frank scored four goals (it was actually three) and Lester had two (actually one).

But it’s his description of what happened in the stands and before the game that I’m chiefly concerned with:

[Those arriving late] found their seats occupied by a swarm of loggers who had taken over part of the reserved section and didn’t care to be disturbed. Nor were they in any shape to be disturbed. Joe Patrick, who was there with Grace, was a little embarrassed, as he had passed out 50 rush-seat tickets up at the camps, and most of these were his boys. ”Unfortunately,” recorded the visiting Rossland reporter, “the opening ceremony featuring the Mayors of Nelson and Rossland was marred by the bawdy behavior of some of the local fans, who had arrived inebriated. Two of them got into a fist fight and fell out of the stands, delaying the start of the contest … ” [ellipsis in original]

The Rossland Miner, which probably did not have a reporter at the game, wrote no such thing. Instead, all the paper said was:

The Rossland and Nelson senior teams played a game of hockey at Nelson on Monday evening, before a good sized audience, and the score was 14 to 1 in favor of the Nelson team. The Golden City boys [i.e. Rossland] received as bad a whipping as they recently gave to the Trail team, when the score was 13 to nil in their favor. It will have the effect of making the home team practice more and make them strengthen the weak places in the lineup. It was the first league game of the season.

Nor did the Nelson Daily News account the following day mention a pre-game disturbance, although it did say there was “a little difficulty last night over the reserved seats but it was only such as might be expected in connection with a first night. The management, however, did all it could to make things right and it can be taken for granted that no trouble of the same kind will ever occur again.”

The specific trouble wasn’t described, so Whitehead seems to have taken the liberty of inventing some details. (Whitehead invented something else in his previous book, Cyclone Taylor: A Hockey Legend, namely a quote around how Taylor got his nickname, which is the subject of a separate post.)

Still searching for

In addition to the above, a number of things in Whitehead’s Patricks book might have happened but can’t be corroborated, or their origin can’t be found. Some of these bits probably came from Lester Patrick’s memoir. Other stuff Whitehead might have made up. I can’t be sure.

• On p. 42, Whitehead has Lester en route to Nelson in 1907 and meeting a man who got on the train in Medicine Hat. “Although this gentleman’s name is long forgotten, Lester recalled him many years later as a ‘pleasant enough gentleman’ from some Calgary law firm who was making the trip to Nelson to defend a client in a murder case.” Whitehead added that the case involved a shooting in the Manhattan saloon that left two people dead.

However, that incident didn’t take place until Dec. 23, 1911, by which time Lester had already moved to Victoria. The suspect, Albert Balsom, was represented by A. Dunbar Taylor, KC and Fred C. Moffatt. Moffatt was a Nelson man while Taylor was from Vancouver. There’s no sign that Taylor ever appeared in Nelson on any other matter.

My best guess is that Lester was talking about a different lawyer and a different case, yet Whitehead for some reason decided Lester must have been referring to the Manhattan saloon shooting, which happens to be mentioned in Nelson: Queen City of the Kootenays.

• On p. 53, Whitehead reports the Patricks receiving a telegram on Dec. 23, 1909 that said the No. 1 camp of the Patrick Lumber Co. had burned to the ground. In his Boston Globe memoir, Frank wrote that “In the winter of 1909 all our camps, with horse, supplies and a good bit of timber, burned to the ground.” It may have happened, but the incident wasn’t reported in any newspaper at the time.

• On p. 56, Whitehead quotes a letter to the editor of the Nelson Daily News, circa 1908, complaining about the “improper public behavior” of the women of the city’s red light district, who strolling about town on Sunday afternoons “both shocks and embarrasses us, and something should be done about it.”

While searches of digitized newspapers don’t always find everything, none of those phrases show up as described.

• On p. 58, immediately prior to describing the first hockey game at the Hall Mines Rink in Nelson in January 1909, Whitehead mentions N.J. Cavanaugh, “a local man who had created a stir the previous summer by bringing a gold brick weighing 465 ounces from his nearby Sheep Creek mine … The huge lump of gold was valued at $17,000, a small fortune in those days.”

Whitehead said Cavanaugh owned a 1908 Franklin, which overheated and stalled en route to the aforementioned game, “and as reported in the next week’s social notes it was last seen sitting alone on the dirt road, with its revolutionary folding top collapsed like a shroud. It is not known whether Mr. Cavanaugh made it to the rink.”

Nicholas J. Cavanaugh was real, but I could find no note in the newspaper about his car getting stuck. In fact, it’s doubtful whether there were any cars in Nelson at the time, or during the whole time the Patricks lived there, from 1907-11. Paul Nipon had the first licensed auto in Nelson and its arrival was announced in the Daily News of July 15, 1912. However, it was described as the “first automobile to be seen in Nelson in recent years,” leaving open the possibility that there had been an earlier one.

Cavanaugh was indeed involved with the Sheep Creek mining camp, but I haven’t found any other sign of the gold brick that supposedly caused a stir. The source of that story is unknown. Whitehead apparently visited Nelson around 1979 while writing his book and spoke with Syd Desireau, a Nelson-born member of the Vancouver Millionaires. Perhaps he gleaned some stories that weren’t recorded elsewhere.

• On p. 94, Whitehead quotes “the local paper,” i.e. the Nelson Daily News, on the departure of the Patrick family in 1911: “the West Coast’s gain is Nelson’s loss …” [ellipsis in original].

There is no sign of this phrase in the digitized Daily News. The closest thing is in the April 13, 1911 edition, where Nelson mayor Harold Selous and board of trade president J.L. Buchan wrote: “We feel that citizens of your stamp are very hard to replace in any community and that Nelson’s loss is indeed Vancouver’s gain.”

But they weren’t talking about the Patricks — those words were about railway contractor W.P. Tierney!

• On p. 129, Whitehead quotes a 1967 New York Times column by Arthur Daley paying tribute to the Patricks: “They should have a monument raised in their memory for that one idea alone [the playoff system]. A mere one-tenth of one per cent of what the NFL alone has earned from it would provide a life-size sculpture of purest marble, with enough left over to stock a franchise.”

The full Times archive is available online, but no such quote can be found. Nor can I find it anywhere else, except in an Archie McDonald column in The Vancouver Sun of May 18, 1985, quoting Whitehead’s book.

• On p. 220, Whitehead described a game between New York and Boston in which Eddie Shore struck Phil Watson in the head with his stick.

Whitehead wrote that Lester Patrick was so enraged with the way referee Clarence Campbell handled the situation that he complained to NHL president Frank Calder, who banished Campbell to the minor leagues.

While Lester was definitely upset about the incident, it did not lead directly to Campbell’s ouster from the NHL, which happened a couple of seasons later and was probably the culmination of many incidents. More about that here.

• On p. 251, Whitehead quotes an anonymous Victoria reporter: “The world of hockey seemed to have converged in front of the flower-laded Communion table [at Lester Patrick’s funeral], to pay homage to the memory of a man and an era.” This might have been something the reporter told Whitehead directly, for there is no sign of it in print elsewhere.

Although I haven’t fact-checked every page, these discrepancies are more than enough to give me pause about the book’s overall trustworthiness. While I wouldn’t necessarily discourage anyone from reading it, I would caution that its contents should be taken with fistfuls of salt.

great history from the west denied in the rich east now finally nhl closed canada from the whl